Paying students to serve lunches during school hours. Bringing retired teachers back to the classroom. Hiring bus drivers for janitorial duties. Shortening in-person instruction to four days a week.

Across the country, these are some of the short-term solutions to a nationwide shortage of school staff at all levels – teachers, administrators, food workers, custodial staff, bus drivers and more – school districts have put into place as they struggle with a combination of sick outages brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, a wave of teacher retirements, employee burnout and back-and-forths with unions.

The crisis will worsen as some states begin to head into colder temperatures and flu season, begins, administrators in Midwestern districts say. Regardless of geography, superintendents and other school leaders all concede there are not enough workers in any pipeline to readily replace outgoing or sick school employees.

By the end of this current calendar year, according to a survey from RAND, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization, nearly one in four teachers surveyed in early 2021 said they were likely to quit their jobs and be out of the classroom. But school officials across the country say the shortage stretches beyond teachers, and includes bus drivers, maintenance staff and more.

“[Staffing is] one of the most important, if not the most important, challenges that we’re facing,” Louisiana State Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley told the PBS NewsHour. “You can have the best programs in the world and the highest level curriculum; but if you don’t have a highly effective teacher in that classroom, you’re not going to get the results for that kid that he or she needs and deserves.”

Filling the staffing gaps

For many schools across the country, shortages start in the classroom. Teacher shortages before the pandemic were already an issue. COVID-19 made it worse. When the National Education Association surveyed nearly 2,700 teachers in June, 32 percent said the pandemic prompted them to leave teaching earlier than they’d planned. It’s also affected how many people are entering the profession.

According to the Missouri Department of Education, the number of aspiring educators enrolling in teacher-preparation programs in the state has dropped by 25 percent while the average rate of teachers leaving their jobs for the last six years sits at 11 percent, higher than the national average.

In St. Louis, which houses one of Missouri’s largest public school districts with around 20,000 students, schools need 114 teachers and 164 support staff which includes nurses, social workers, counselors and aides. It also needs 27 substitutes, 58 custodians and 43 security guards, according to George Sells, director of communications for St. Louis Public Schools.

“Most districts have had teacher shortages for some time but they have been magnified by the COVID-19 outbreak,” Sells told the NewsHour via email.

In Michigan, addressing the teacher shortage is the most urgent challenge facing the state’s public schools, as it is for many states across the nation right now, Michigan’s State Superintendent Dr. Michael F. Rice told the State Board of Education earlier this month.

Michigan schools in particular need a significant investment of $300 million to $500 million over five years to address the systemic challenges causing the teacher shortage and to begin recruiting and retaining sufficient numbers of high-quality educators, Rice said.

Some efforts from the Michigan Department of Education include waivers to help former educators become recertified, reaching out to certified educators not currently teaching, and alternative teacher certification programs to support aspiring teachers, including paraprofessionals and support staff.

“We have begun to make progress with significant investments in early childhood learning, literacy, children’s mental health, and school funding,” Rice said in a statement. “That said, we need to work to fund major teacher recruitment and retention efforts.”

This problem is not new. In 2017, the Michigan Association of Superintendents and Administrators (MASA) recognized that many Michigan school districts were struggling with teacher shortages and created an Educator Shortage Workgroup to develop member-driven solutions. The next year, this workgroup released a toolkit of short-term strategies districts could use, and released a strategic plan for revitalizing education careers the year after that.

But before they could implement those ideas, the pandemic came, and Michigan’s preexisting condition of teacher shortages was exacerbated.

“Teachers, as well as building and district leaders, are retiring at unprecedented levels, and there simply aren’t enough new educators to replace them,” Tina Kerr, executive director of MASA, told the PBS NewsHour. “We’re seeing schools close, the state is begging retirees to return, and too many students — especially students of color and those living in poverty — are being taught by long-term subs, and we’re seeing a shortage of them too.

“This situation isn’t just a result of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Kerr added, “but it’s certainly been exacerbated by it. The pandemic has shone a bright light on many issues within our education system that were already there and that we, and others, have been working to combat – but there’s no silver bullet solution.”

Sells, of St. Louis Public Schools, says the district has increased pay for teachers for covering classes that are not theirs and raised the pay for substitute teachers. Sells said St. Louis Public Schools has had to get creative about how to fill other gaps in support staff.

“We have made arrangements with the unions involved and our third party bus company to allow bus drivers to do custodial work during the day between driving shifts,” Sells said, noting that these kinds of shortages – custodians, bus drivers and security officer – have definitely been pandemic-related.

“Long term, we’re worried that it’s creating a trust crisis on top of a health crisis.”

In early November, the Missouri Department of Education launched TeachMO.org, a new recruitment tool the state hopes will help draw in more teacher candidates. With some districts using administrators to step in to teach classes, the state is also investing more than $50 million to recruit and retain educators over the next three years.

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, staffing shortages extend “across all job categories,” Superintendent Jeanice Swift told the NewsHour. “Teachers, paraprofessionals, support staff. Our biggest and most profound shortages are among those hourly employees that keep the system operating every day. So the bus drivers, the bus monitors, the lunchroom supervisors, the child care workers.”

The type of people who tend to work in these often part time support jobs – retired people, older people, parents and grandparents – have changed their availability because of the risks of COVID-19 and changes in school schedules and personal responsibilities, Swift said.

Dearborn Public Schools, located outside of Detroit, have not had to close any of their 38 schools due to staff shortages, in part because they took a proactive approach and hired additional teachers last winter to support their virtual school and in anticipation of a teacher shortage across the state. They have hired 150 teachers since January, according to the superintendent, although they are still struggling with some positions that are hard to fill like special education paraprofessionals.

But the teachers who are working there are at risk of burnout, something the district’s superintendent says he is cognizant of and working to prevent.

“We understand that along with the stress that one may be feeling at work they also may have a very stressful situation at home. We have attempted to lessen the workload for staff and we are working on wellness models and programs for staff,” Glenn Maleyko, superintendent of Dearborn Public Schools told the NewsHour.

“Teachers and staff are faced with a vast increase in the amount and type of social emotional interventions needed by all stakeholders [including] staff, students, parents, and community. As always, but now exasperated, staff juggle parenting of children, provide care for aging parents, societal pressures, and their own inability for self-care,” Maleyko said.

And at least in one district where adults can’t step into vacancies, students are up for recruitment.

A little under 30 miles from St. Louis in Hot Springs, Missouri, the Northwest R1 School District is offering some of its own high school students compensation help with its support-staff shortages, Northwest Chief Human Resources Officer Mark Catalane said.

“We were struggling prior to COVID but once COVID hit it made it worse,” Catalane said.

The district is down a total of nine people from custodial, school food and before and after school care staff. Catalane said they will employ more than nine students to “tailor it around their educational needs.”

Students who are hired will get paid hourly at the same rate as all other hourly employees, Catalane said. They will not have to work holidays or weekends, and if their assignment is at another school, the district will provide transportation. Catalane said the idea has already garnered positive feedback from the community while also helping the district during a difficult time.

“Twenty-five students applied and the majority will get some hours,” he said.

The solution has also sparked interest across the country with inquiries about the new method coming from school districts in Iowa and Alaska, Catalane said. Sharing ideas with other school officials facing the same barriers is the least leaders can do to lessen the impact students may feel both inside and outside of the classroom, he added.

“We’re all trying to service our kids as best we can,” he said.

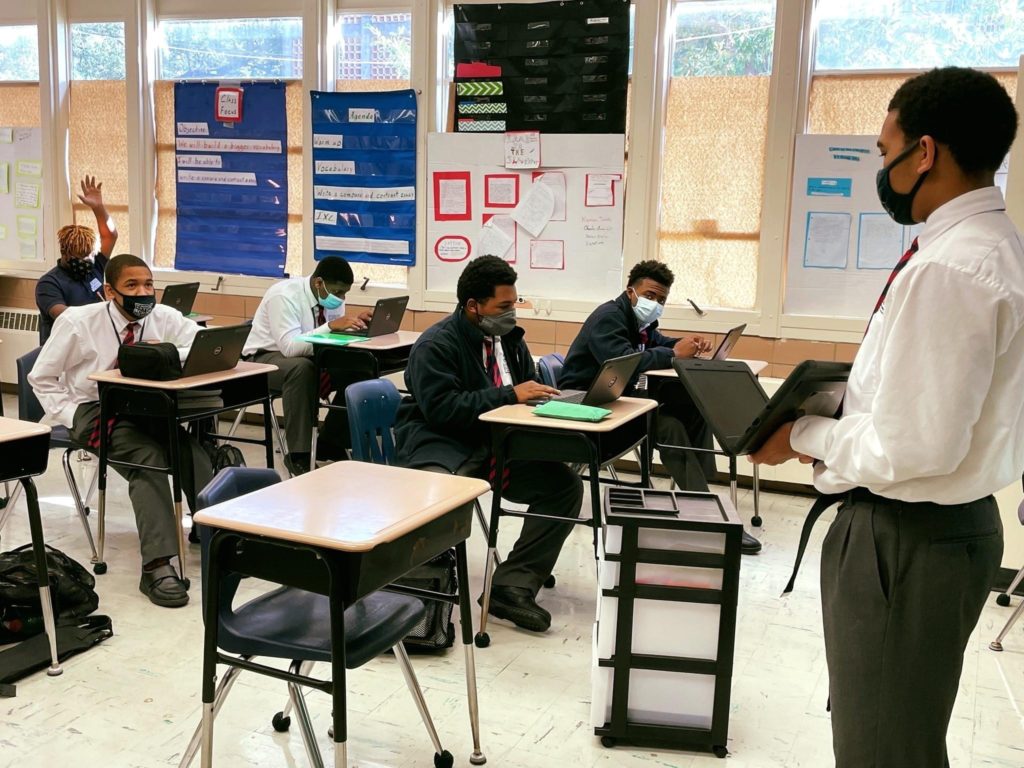

Students at the Arthur School in New Orleans return to class in a city where the impact of teacher turnover is especially acute in schools that serve the neediest students. Photo by Taslin Alfonzo/ New Orleans Public Schools

Retired teachers back on duty

In California, where a COVID-19 emergency declaration remains in place, retired teachers are returning to the classroom in some school districts to help alleviate the teacher shortage.

Barry Jager, associate superintendent of human resources and employee relations at Clovis Unified School District in the San Joaquin Valley, said teachers who had left the classroom are among those now serving as critical help to staff at some of the district’s approximately 50 schools, which includes elementary, high school and alternative education sites.

Substitute teachers play a “pivotal role,” Jager said, in helping fill in for teachers who oversee extracurricular activities or who need to undergo professional development training now that the district’s roughly 44,000 students are back in classrooms.

“We always needed and relied heavily on our amazing subs. But right now, with individuals — for their own personal reasons or other financial related reasons — they’re not getting into the workforce as they have in the past,” Jager told the NewsHour.

In August, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order that made it easier for retirees to return to the classroom by removing the requirement for the retiree to be approved by a school board, but the teachers are still limited in how much they earn post-retirement.

It was part of the governor’s response to the lack of teachers and classified staff across the state and to alleviate school needs amid rising coronavirus infections in the state. Retired teachers can now return to work 180 calendar days after their final day of teaching. Under the order, which will last as long as the state determines the pandemic is an emergency, school districts who request and accept retirees must show that there is a critical need for the staff at their schools.

Navigating post-retirement rules is among the newer tactics the state is trying, but officials knew shortages existed before the pandemic.

Cheryl Cotton, deputy superintendent of the Instruction, Measurement and Administration Branch of the California Department of Education, told the NewsHour that staffing issues and resignations are hitting schools just as they are currently hitting other professions and industries. But, as with other districts in the U.S., the number of educators entering the teaching profession had already been steadily declining over the previous years. She cited barriers in credential programs and testing requirements as possibly playing a role.

The state has focused on helping school districts retain and recruit teachers through “Educator Effectiveness Funds” that are allocated to local school districts to train and mentor teachers and support professional learning.

“This is a challenge that we’re seeing across our labor market, not just in education, not just in schools, but it is impacting schools and students and families in a very serious way,” Cotton said.

The shortage of substitutes, and by extension the lack of trained teachers statewide, is a wide-ranging problem across the San Joaquin Valley as well as the state, according to education officials. Jager said a separate challenge is competing for the same pool of substitutes in a single region.

He said Clovis Unified has upwards of 500 substitute teachers in its database and has even added to it in recent months. But Clovis is among several school districts located in the Fresno-Clovis metropolitan area that offer substitute positions, creating a competitive environment.

Jager said Clovis Unified recently increased daily substitute pay to $165 and $175 a day for substitutes who stay long-term.

Retirees aren’t the only ones stepping in. School officials in Clovis Unified are also cold-calling substitute applicants in order to help them complete the application process. And administrators are working with nearby universities like Fresno Pacific University and California State University at Fresno to reach students who may want to become teachers and help get them through credential programs or into teaching positions. Jager thinks the work the district has done to recruit teachers will pay off.

“We will continue to seek long-term goals on how we can keep competitive wages. We will work to see how we can bring individuals into our workforce. We’re looking at ways for some of our instructional aide positions that will be going to full time positions,” Jager said. “We feel that, you know, people will look forward to an opportunity to apply into an instructional position that has additional hours with benefits.”

The demand for daily substitute teachers skyrocketed in the last six months in Clovis, according to Jager. He said the rush to fill positions wasn’t as necessary last year with students learning virtually, from home.

The situation has caused schools to think outside the box to fill gaps in teaching. In desperate situations, Jager said school administrators, including himself, have taught classes at elementary and high schools.

“We’ve really left no stone unturned in regards to finding ways to make sure that our students have a safe and positive learning environment,” Jager said.

Jager hopes to find some remedy at a job fair scheduled for January, where not only will the district seek to fill open teaching positions but also classified positions like bus drivers and catering staff.

Similar openings are for now going unfilled in the Visalia Unified School District, 40 miles south. District spokeswoman Kim Batty said the school district is struggling to hire classified staff such as classroom aides, special education aides, bus drivers, cafeteria workers and nurses.

She added that the school district is close to being fully staffed with certificated teachers, but the district still sees a need to hire fully-credentialed teachers who can help mentor other teachers at the schools in understanding “social and emotional learning and teaching skills.”

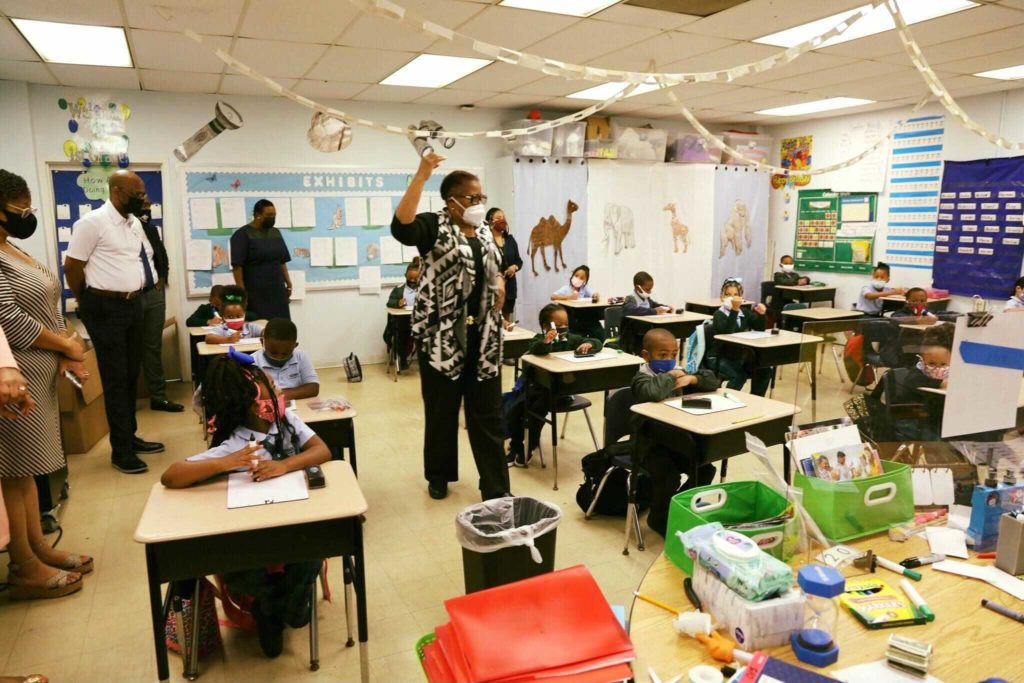

Students at Martin Behrman Elementary in New Orleans are eager learners in a city where 46 percent of teachers have three or fewer years of experience. Photo by Taslin Alfonzo/New Orleans Public Schools

Creating a ‘trust crisis’

Mental and emotional health is one of the main concerns among the 4,000 teachers that make up the Fresno Unified School District.

Nikki Henry, a district spokeswoman, told the NewsHour that the district, like others across the country, is seeing a high demand for substitutes. But an internal division between the Fresno Teachers Association union and the district reveals an unclear method of addressing the teachers’ needs at a time of such shortages and demands brought on by the pandemic.

The union president, Manuel Bonilla, believes the district should redesign its vision for school teachers, for example by giving teachers extra time to prepare during the work day. Union leadership is in talks with the district to address grievances among teachers who say they’re overworked.

Bonilla said the district has so far stuck to old practices and regular expectations for teachers at the same time that teachers report dealing with added stress, less preparation time and new health protocols in the classroom.

“The reason why people feel this way is because [the district] is not recognizing the reality of the situation. [The district] is pretending like this is a normal year,” Bonilla said. “That’s a frustrating component. Here we have an opportunity to do something different and we’re not.”

The union has proposed to the district cutting back on the number of meetings teachers must attend during the year with administrators. The district, in public forums and in statements to local media, said any agreement between the district and the union should not “compromise student’s instructional minutes with their teachers or change and disrupt schedules” of students and families.

Bonilla said their proposal does not impact student learning time.

“It just feels like a compliance-based system as opposed to a system that trusts the expertise of its educators,” Bonilla said.

The district did not immediately respond to questions about its negotiations with the union.

Bonilla said without more time for teacher preparation and breathing room in between lessons, the issues for teachers will continue to cascade. Already, 67 percent of Fresno teachers have considered early retirement, stress leave or a change of career, according to an internal survey conducted by the union. It’s a high number, but Bonilla said he’s not surprised given the current circumstances.

The lack of substitutes means teachers sometimes must oversee more students than they’re used to, and that means they have less time during school hours to get preparation work done. Bonilla said that means teachers are taking home extra work and never fully catching up, and some teachers have reported taking sick days to do work at home.

He said teachers are less worried about an increase in pay, than they are in getting the adequate amount of time to provide what educators see as quality instruction.

“Long term, we’re worried that it’s creating a trust crisis on top of a health crisis,” Bonilla said by phone. “If the district leadership, and the school board superintendent, if they’re unwilling to listen, if they’re unwilling to pivot to address the needs of educators in a crisis moment and probably the deepest needs educators have ever felt, what does that say to teachers? How else are they supposed to interpret that for when times are better?”

In Kansas City, the school district hired a retention coach so teachers have a point person to turn to when they are feeling overwhelmed. “They work with teachers, they can go in and work directly with the students, drop in and sub for an hour and they can find out what the teacher needs,” said Elle Moxely, public relations coordinator for Kansas City Public Schools.

Like St. Louis Public Schools, Kansas City’s district plans to pay teachers more for filling in to teach classes they don’t normally teach. Moxely said they have also used COVID-19 relief funds to hire building substitute teachers, which are employed by the school system rather than an agency, allowing them to have access to benefits. But Moxley notes that solutions are needed not just for teachers but for all staff and faculty.

“We have increased pay for our drivers so they can make pretty close to full-time wages,” she said. “There are a lot of people making sure school is still school.”

According to a report from the Michigan Department of Education, based on Department of Education data, the number of students enrolled in Michigan teacher preparation programs in the 2019-2020 school year was 9,760 — a 47 percent drop from the 18,483 enrolled in the 2013-2014 school year. The number of students completing these programs in 2019-2020 was 2,258, dropping more than 50 percent from 2013-2014.

In order to help develop the pipeline for new teachers, Swift said that Ann Arbor Public Schools (AAPS) has longstanding partnerships with the University of Michigan School of Education and other university education programs to train student teachers, conduct research, and to serve as teaching and lab schools. AAPS is also part of a newer program at Michigan State University, called Grow Your Own, which helps paraprofessionals, teacher assistants, parents, and other workers who are already part of the school community get their teaching certification while working, with almost all of their expenses paid.

While AAPS does recruit teachers nationally, it sometimes has difficulty convincing people from other places to move to Michigan. “The beauty of this program,” Swift, the district’s superintendent said, “is that these are individuals who already love our schools. They already love our children. They already know what the classroom life is like. So there’s no surprise there. So we love this program because it is very promising and also very promising to increase diversity among our teaching staff.”

Swift said that it is important for leaders at the state and federal levels to understand that these exacerbated needs around labor, staffing, support for students with their learning, mental health, and physical health will not end when COVID-19 ends. Rather, she says, it represents a fundamental shift in the nature of education and a recognition of the importance of public schools.

“As much as we all want to say, ‘maybe the pandemic will be over in the coming weeks,’ for public schools, our work will extend,” Swift said. “So how do we recognize the gifts that [teachers] bring and the important cornerstone that that public schools are to our very democracy, to the foundation of our democracy, and how to ensure that that quality endures even through these shifts that are going to occur around Covid?”

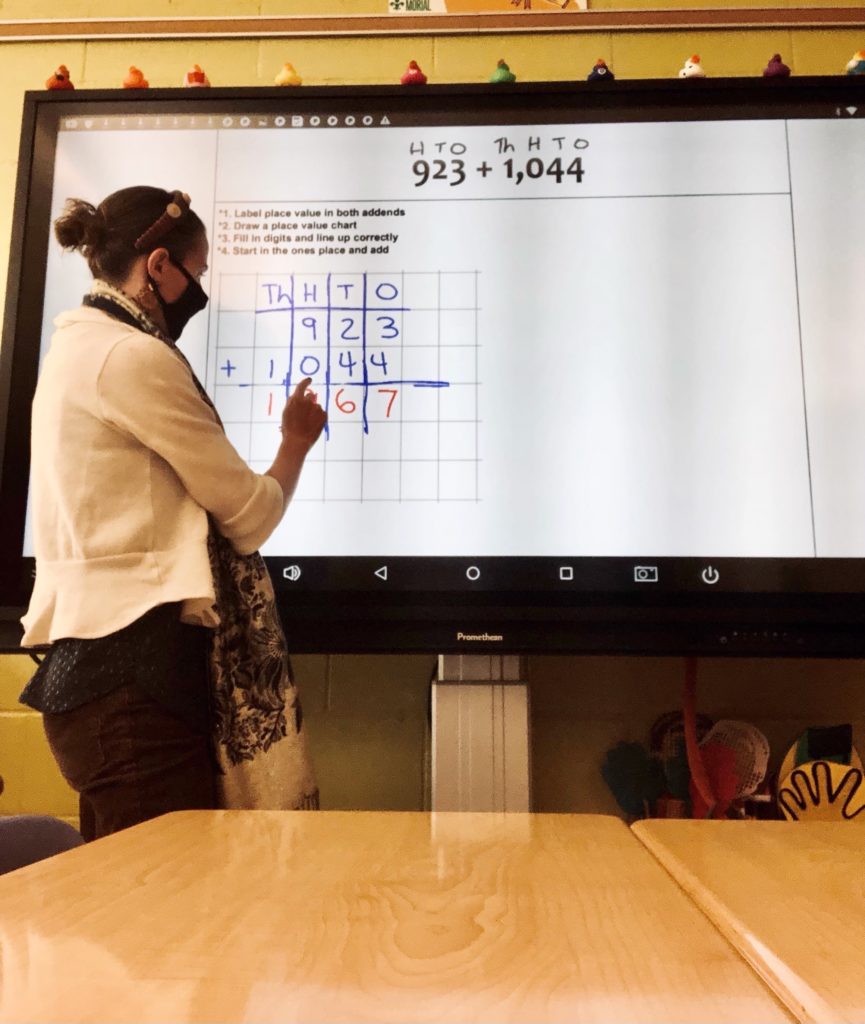

Veteran special education teacher Lauren Jewett says teachers in New Orleans were in survival mode following nearly two years of classroom disruptions which took a toll on educators. Photo by Lauren Jewett

Turnover turmoil

But with districts recruiting new teachers, desperately trying to hold onto existing ones, and rotating substitutes and volunteers in between, leaders are concerned about students who may not build critical bonds with the educational process when they constantly have to deal with new, temporary faces.

The impact of teacher turnover is especially acute in schools that serve the neediest students. In New Orleans, where nearly nine in 10 students receive free or reduced lunch, 46 percent of teachers are novices, with three or fewer years of experience, according to a 2019 report from the Greater New Orleans Foundation. This compares to just 18 percent for the state as a whole.

There have been multiple setbacks with nearly two years of classroom turmoil, virtual learning, and school closures which upended education for nearly 700,000 children enrolled in public schools across the state. Teachers have faced unbelievable struggles. Hurricane Ida hit in August at the start of the school year as the state was experiencing a fourth wave of Covid caused by the Delta variant.

“The toll of covid and pandemic teaching compounded with natural disasters is a lot to deal with. A lot of us haven’t had a summer,” said 34-year-old special education teacher, Lauren Jewett. “We had whole classes going out on quarantine. We were just in survival mode.”

Doris Voitier, superintendent of the St. Bernard Parish School District and a veteran of 50 years in the profession, said the current education landscape is unlike anything she has seen.

“I have never had as much of a struggle to adequately staff our programs as I have the past year,” Voitier, a member of the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, told the Associated Press. The shortage has a direct impact on day-to-day learning, with 24 percent of teachers either uncertified or teaching outside their field of expertise, according to figures provided by the state department of education.

The outlook to fill the pipeline is not good. Fewer people seem to be going into teaching in Louisiana. The number of prospective teachers enrolled in LSU’s teacher preparation programs shrunk by more than 60 percent over the past decade, from 960 candidates in 2011 to 376 who are currently enrolled, and nearly 40 percent over just the past five years, according to enrollment figures provided by the LSU School of Education. The shrinking pool of teacher candidates leaves the state, usually at the bottom of most educational rankings, in dire straits, especially given the high and accelerating rate of experienced teachers leaving the classroom.

In Louisiana, the classroom teacher shortage is growing worse, with rising retirements and declining ranks of new teachers in districts around the state. The Louisiana Department of Education figures released last year show nearly 50 percent of teachers left their jobs in their first five years. Retirements of teachers and other school personnel shot up 25 percent from 2020 to 2021, according to data compiled by the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana. More than 2,100 K-12 employees retired after the 2019-20 school year, increasing to 2,686 a year later.

The problem was compounded as Louisiana schools grappled with pandemic surges and catastrophic hurricanes over the last two years. Education leaders worry the problem is at a critical stage.

“I would definitely say it’s a concern. It’s a concern both from the recruitment standpoint and the retention standpoint,” Louisiana State Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley told the PBS NewsHour. “Our teachers are acting with urgency to try to take care of the needs of their students. Our teachers have done hero’s work, but they’re tired and the expectations remain high because the work is so critically important.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eVmcKkrdOipqdno5i1sLvLrGSam6KkwLR506GcZpufqru1vthmmKudXajBs8HGoKOippdiwbB5xaKlnWWjqa6nsoyhnKudo2LEqcU%3D